It wasn’t until researchers extracted neural stem cells from adult mouse brains and grew them in cell culture that scientists showed these precursor cells could divide and differentiate into new neurons. It started to look like neurogenesis plays a key role in learning and neuroplasticity – at least in some brain regions in a few animal species.Įven so, neuroscientists were skeptical that many nerve cells could be renewed in the adult brain evidence was scant that dividing cells in mammalian brains produced new neurons, as opposed to other cell types. Then researchers discovered that new neurons are also born throughout life in the songbird brain, a species scientists use as a model for studying vocal learning. Neurogenesis – the production of new neurons – was previously thought to only occur during embryonic life, a time of extremely rapid brain growth and expansion, and the rodent findings were met with considerable skepticism.

This approach led to the startling discovery in the 1960s that rodent brains actually could generate new neurons. Just over half a century ago, researchers devised a way to study proliferation of cells in the mature brain, based on techniques to incorporate a radioactive label into new cells as they divide. And I suspect other labs that focus on conditions including drug addiction, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder are thinking about what the UCSF study means for their investigations, too. If the new study is right, and human brains for the most part don’t add new neurons after infancy, researchers like me need to reconsider the validity of the animal models we use to understand various brain conditions – in my case temporal lobe epilepsy. Like many labs, part of our work is based on a foundational belief that the hippocampus is a brain region where new neurons are born throughout life. It has direct implications for the research my lab does: We transplant young neurons into damaged brain areas in mice in an attempt to treat epileptic seizures and the damage they’ve caused.

But now a controversial new study from the University of California, San Francisco, casts doubt on whether many neurons are added to the human brain after birth.Īs a translational neuroscientist, this work immediately piqued my interest.

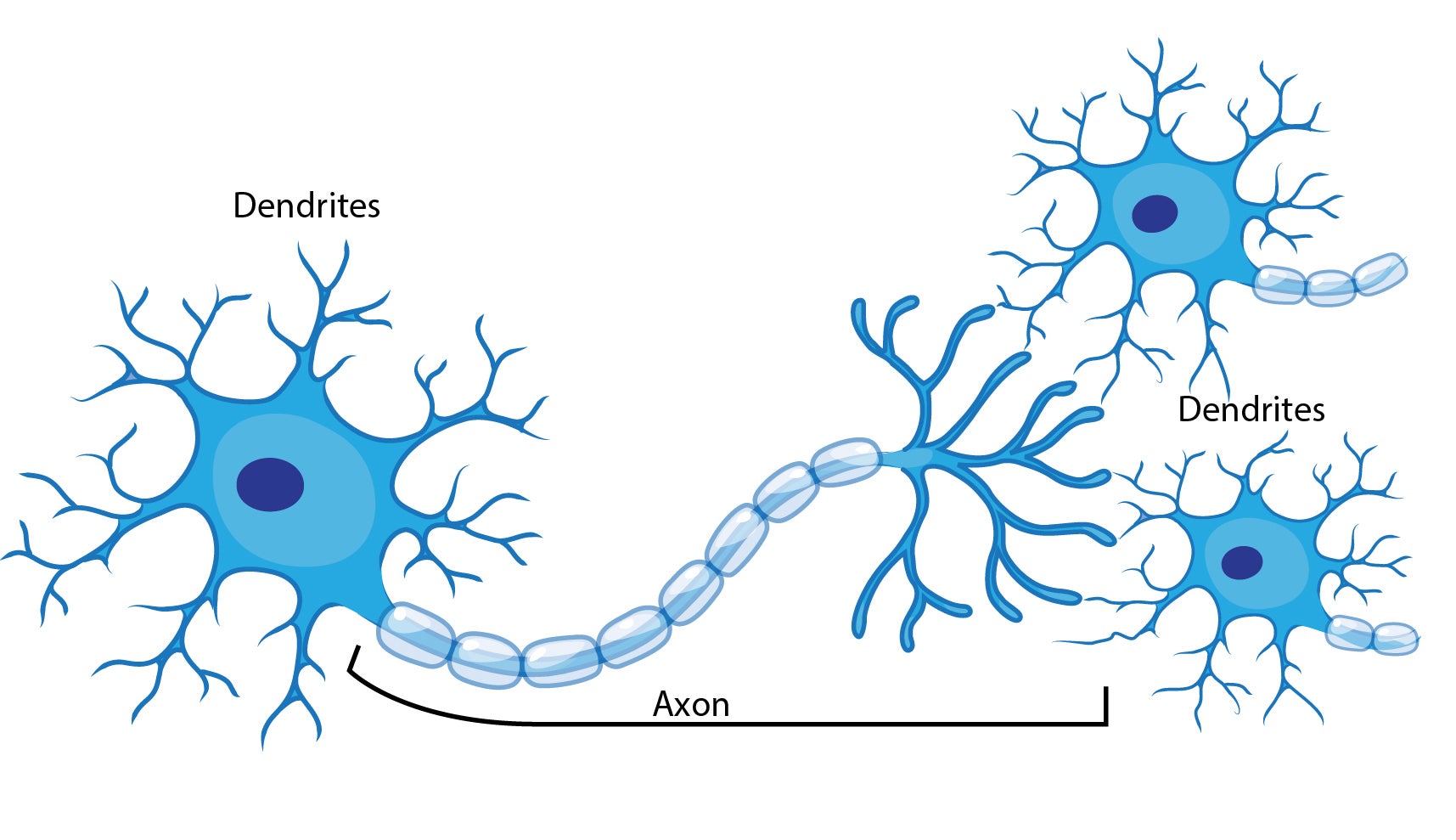

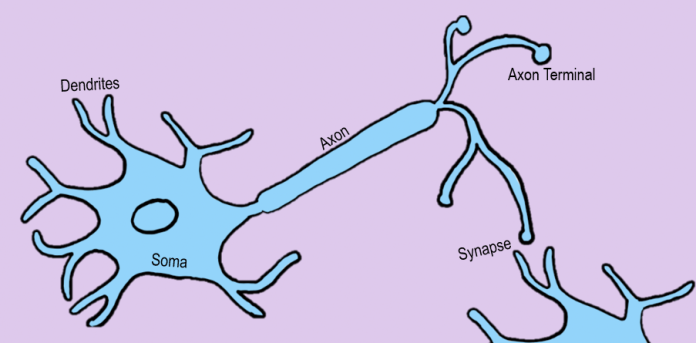

Scientists have known for about two decades that some neurons – the fundamental cells in the brain that transmit signals – are generated throughout life.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)